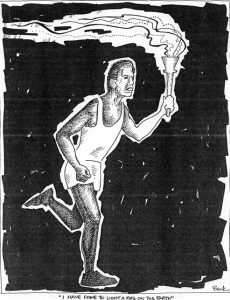

I come to set fire to the earth

August 14, 2016

TWENTIETH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME

Jeremiah 38:4-6, 8-10

Jeremiah saved from the cistern

Psalm 40: 2-4, 18

He drew me out of the pit!

Hebrews 12:1-4

Persevere in running the race

Luke 12:49-53

I come to set fire to the earth

http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/081416.cfm

Just in time for the Olympics, the letter to the Hebrews speaks of running the race that lies before us, with our eyes fixed on Jesus. However, with Jebrews we should probably be thinking of the original Olympics.

Just in time for the Olympics, the letter to the Hebrews speaks of running the race that lies before us, with our eyes fixed on Jesus. However, with Jebrews we should probably be thinking of the original Olympics.

In addition to competition, today we also hear about contention. We are always a bit unnerved when Jesus says, as he does in Luke’s gospel today, that he did not come to bring peace. Not peace, but division. And it doesn’t help much when we learn that in a parallel passage, where Luke speaks of division, Matthew speaks of weaponry. “Do not think that I have come to bring peace upon the earth. I have come to bring not peace but the sword” (Matthew 10:34).

Also, elsewhere Luke actually does mention a sword. At the Supper, recalling the earlier instructions about sending them out two-be-two, he says, “But now one who has a money bag should take it, and likewise a sack, and one who does not have a sword should sell his cloak and buy one” (Luke 22:36). The scholars assure us that he is speaking in metaphors, even though the disciples take it literally.

We also remember a metaphorical sword earlier in the story. You will recall the prophecy of Simeon, when he tells Mary, newly mother of the child Jesus, “Behold, this child is destined for the fall and rise of many in Israel, and to be a sign that will be contradicted—and you yourself a sword will pierce—so that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed” (Luke 2:34). The promise of coming divisions is unmistakable.

What does Luke have in mind? That the message of Jesus should be a refining fire, a source of contention, even among families, fits well within the prophetic tradition. And today we see a prominent example of that tradition, in the story of Jeremiah in the muddy cistern. Clearly, some want him out of the way.

Jeremiah lived in perilous times. Judah was under siege by the army of Babylon. He is in special trouble because he is publicly speaking against the war, even as they are engaged in it. Judah had no hope of winning the war. It was obvious, but Jeremiah said it out loud. He was accused of subverting the war effort. The leaders who opposed him cited the presence of Yahweh in the Temple. Surely God would save them. Jeremiah thought not. Charges of heresy were added to those of treason.

In the episode we hear, events are nearing their end. Unwilling to endure him any further, the leaders, with the permission of the king, dispose of him in one of the many cisterns. Nearly dry, it is full of mud. Jeremiah is spared by the intervention of an official, an African working in the Judah court, named Ebed-melech, literally, “servant of the king.” Pleading with the king, he produces a change of mind, and permission to rescue the prophet. He succeeds, and all is well. Until the next time.

The story of Jeremiah demonstrates the kind of conflict that the prophet brings to the social situation. He is a cause for division, it would seem. Yet what he actually does is simply to bring to the surface a division already there. Making it public is his gift and his fault. The hidden division, known by all, is by tacit agreement not mentioned. I am reminded of a special kind of secret—the secret that everybody knows. It lives by the common, unspoken agreement to keep it unspoken. The prophet, however, refuses to keep silent.

For reflection: Isn’t it better for the prophet to keep silent, rather than occasion a public disturbance?

Father Beck is professor emeritus of religious studies at Loras College, Dubuque.